【双语阅读】BRAC的商业一面.

2017-08-14 437阅读

Business;Face value;

BRAC in business

Fazle Hasan Abed has built one of the world&aposs most commercially-minded and successful NGOs;

Smiling and dapper, Fazle Hasan Abed hardly seems like a revolutionary. A Bangladeshi educated in Britain, an admirer of Shakespeare and Joyce, and a former accountant at Shell, he is the son of a distinguished family: his maternal grandfather was a minister in the colonial government of Bengal; a great-uncle was the first Bengali to serve in the governor of Bengal&aposs executive council. This week he received a very traditional distinction of his own: a knighthood. Yet the organisation he founded, and for which his knighthood is a gong of respect, has probably done more than any single body to upend the traditions of misery and poverty in Bangladesh. Called BRAC, it is by most measures the largest, fastest-growing non-governmental organisation (NGO) in the world—and one of the most businesslike.

Although Mohammed Yunus won the Nobel peace prize in 2006 for helping the poor, his Grameen Bank was neither the first nor the largest microfinance lender in his native Bangladesh; BRAC was. Its microfinance operation disburses about $1 billion a year. But this is only part of what it does: it is also an internet-service provider; it has a university; its primary schools educate 11% of Bangladesh&aposs children. It runs feed mills, chicken farms, tea plantations and packaging factories. BRAC has shown that NGOs do not need to be small and that a little-known institution from a poor country can outgun famous Western charities. In a book on BRAC entitled “Freedom from Want”, Ian Smillie calls it “undoubtedly the largest and most variegated social experiment in the developing world. The spread of its work dwarfs any other private, government or non-profit enterprise in its impact on development.”

None of this seemed likely in 1970, when Sir Fazle turned Shell&aposs offices in Chittagong into a ruge for victims of a deadly cyclone. BRAC—which started as an acronym, Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee, and became a motto, “building resources across communities”—surmounted its early troubles by combining two things that rarely go together: running an NGO as a business and taking seriously the social context of poverty.

BRAC earns from its operations about 80% of the money it disburses to the poor (the remainder is aid, mostly from Western donors). It calls a halt to activities that require endless subsidies. At one point, it even tried financing itself from the tiny savings of the poor (ie, no aid at all), though this drastic form of self-help proved a step too far: hardly any lenders or borrowers put themselves forward. From the start, Sir Fazle insisted on brutal honesty about results. BRAC pays far more attention to research and “continuous learning” than do most NGOs. David Korten, author of “When Corporations Rule the World”, called it “as near to a pure example of a learning organisation as one is likely to find.”

What makes BRAC unique is its combination of business methods with a particular view of poverty. Poverty is often regarded primarily as an economic problem which can be alleviated by sending money. Influenced by three “liberation thinkers” fashionable in the 1960s—Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire and Ivan Illich—Sir Fazle recognised that poverty in Bangladeshi villages is also a result of rigid social stratification. In these circumstances, “community development” will help the rich more than the poor; to change the poverty, you have to change the society.

That view might have pointed Sir Fazle towards lt-wing politics. Instead, the revolutionary impetus was channelled through BRAC into development. Women became the institution&aposs focus because they are bottom of the heap and most in need of help: 70% of the children in BRAC schools are girls. Microfinance encourages the poor to save but, unlike the Grameen Bank, BRAC also lends a lot to small companies. Tiny loans may improve the lot of an individual or family but are usually invested in traditional village enterprises, like owning a cow. Sir Fazle&aposs aim of social change requires not growth (in the sense of more of the same) but development (meaning new and different activities). Only businesses create jobs and new forms of productive enterprise.

After 30 years in Bangladesh, BRAC has more or less perfected its way of doing things and is spreading its wings round the developing world. It is already the biggest NGO in Afghanistan, Tanzania and Uganda, overtaking British charities which have been in the latter countries for decades. Coming from a poor country—and a Muslim one, to boot—means it is less likely to be resented or called condescending. Its costs are lower, too: it does not buy large white SUVs or employ large white men.

Its expansion overseas may, however, present BRAC with a new problem. Robert Kaplan, an American writer, says that NGOs fill the void between thousands of villages and a remote, often broken, government. BRAC does this triumphantly in Bangladesh—but it is a Bangladeshi organisation. Whether it can do the same elsewhere remains to be seen.

【中文对照翻译】

商业;商界人物;

BRAC的商业一面

法佐·哈桑·阿比德建立了世界上最具商业头脑的、最成功的NGO组织;

面带微笑、衣冠楚楚的法佐·哈桑·阿比德怎么看也不像是一个革命者。 这个在英国受的教育的孟加拉人是莎士比亚和乔伊斯的粉丝,曾在壳牌公司作过会计,家族显赫: 外祖父是孟加拉殖民政府的一位部长;一位叔祖父是第一个为孟加拉行政会议长官做事的孟加拉人。 本周,阿比德得到了加在自己头上的荣誉——一个很有传统的称号:爵士头衔。 然而,他创建的这个组织——他被授予爵士头衔也是对这个组织的一种敬意——却颠覆了传统,改变了孟加拉一直以来的贫穷和困苦,而且在这方面作出的贡献可能比任何一个单一团体都多。 这个组织叫作BRAC(孟加拉国农村发展委员会),用绝大多数标准衡量都是世界上最大的、成长最迅速的非政府组织(NGO)——而且是最像企业的NGO之一。

虽然2006年获得诺贝尔和平奖的是穆罕默德·尤努斯, 但是他的格莱珉银行既不是孟加拉第一家也不是最大一家小额贷款银行;包揽这两个第一的是BRAC。 它的小额贷款业务每年要发放10亿美元的贷款。 但是这仅仅是它的部分业务:它还是互联网服务的供应商;它拥有一所大学;它办的小学解决了孟加拉11%孩子的受教育问题。 它还经营饲料加工厂、养鸡场、茶叶种植场,还有包装厂。 BRAC的成功表明NGO组织不一定要非常小,而且一个来自穷国、不为人知的机构可以干过西方著名的慈善机构。 伊恩·斯迈利在他专门写BRAC的书《彻底走出饥饿》中将这称作“在发展中国家中无疑是最大规模且最为斑斓的社会实验。 其社会工程的散播广度让其它任何私有的、政府的或是非盈利的企业都相形见拙,为社会发展带来的影响无人能及。

但在1970年却看不出这些,当时的法佐把壳牌公司在吉大港的办公址变成了避难所,接纳在一次恐怖龙卷风中的受害者。 BRAC——分别是“孟加拉,康复,援助,委员会”四个英文单词的首字母,并且演变成一句口号, “建立跨社区资源”——克服了早期遇到的困难,办法是将两件很少能并置的东西结合到了一起: 1.像做生意一样运作一个NGO;2.认真对待贫穷的社会环境。

BRAC向穷人发放的钱款中有80%来自其自主经营(剩下的来自捐助,大多是西方的捐助者)。 它会叫停那些无休止依赖捐助的项目, 甚至还曾一度试着通过穷人的点滴存款来为自己融资(换种说法就是不依赖丁点捐助),尽管这种极端的自助形式后被证明走的太远:几乎没有人主动来存钱或贷款。 从一开始,法佐就坚持公开透明,对于经营业绩毫不隐瞒——即使是很坏的业绩。 BRAC对于调研和“持续学习”的注重要远胜于大多NGO组织。 《当企业统治世界》的作者大卫·科尔顿把BRAC称作“可能是能够找到的最为纯粹的学习型组织”。

BRAC之所以能够独树一帜,在于它的经营手法是与其看待贫穷的独特观点相结合的。 贫穷在多数时候被首先看作是经济问题,可以通过发放金钱得到缓解。 因为受到在1960年代很流行的三位“解放式的思想家”——弗朗兹·法农、保罗弗·莱雷和伊凡·伊里奇——的影响,法佐认识到孟加拉国农村的贫穷问题是源于严格的社会层级。 在这样的环境下,“社区发展”对于富人的帮助要胜于对穷人的帮助;为了改变贫穷状态,你必须改变社会。

这样的观点本来可能会指引法佐走向左翼政治。 而实际情况是,这种革命动力经BRAC的催化转换成了实实在在的发展。 妇女成为了这个机构的主要关注对象,因为她们身处最底层,且最需要帮助:BRAC办的小学里70%是女生。 小额贷款鼓励穷人存钱,但是和格莱珉银行不同之处在于,BRAC也把钱借给小公司。 小额贷款可能会改变一个人或是一个家庭的命运,但是这些钱通常都被投资在传统的农村致富项目上,比如养牛。 法佐改变社会的目标靠的不是增长(是指“同类项目越来越多”),而是发展(意思是“新的不同的生意”)。 只有生意才能创造就业就会,才能产生新形式的、生产力强的企业。

经过在孟加拉30年的发展,BRAC对于自己这套业务之道已多少达到完善,并且正在将触角伸向其它第三世界国家。 它已经超过英国的慈善机构,成为阿富汗、坦桑尼亚、乌干达这几个国家中最大的NGO组织,而后者已经在这些国家经营了几十载。 因为是来自穷国——还是一个穆斯林国家,这意味着BRAC不大可能遭人反感,或被形容为“居高临下的恩施”。 它的花销也同样很低:没有大型的白色越野车,也没雇佣高大的白人。

然而,BRAC在海外的扩张面临着一个新问题。 美国作家罗伯特·卡普兰说,NGO组织填补了一个遥远且经常失灵的政府和成千村庄之间的空白地带。 BRAC在孟加拉胜利地做到了这一点——但是它是孟加拉的组织。 它在其它地方也能这样吗?还有待结果告诉我们。

【双语阅读】BRAC的商业一面 中文翻译部分Business;Face value;

BRAC in business

Fazle Hasan Abed has built one of the world&aposs most commercially-minded and successful NGOs;

Smiling and dapper, Fazle Hasan Abed hardly seems like a revolutionary. A Bangladeshi educated in Britain, an admirer of Shakespeare and Joyce, and a former accountant at Shell, he is the son of a distinguished family: his maternal grandfather was a minister in the colonial government of Bengal; a great-uncle was the first Bengali to serve in the governor of Bengal&aposs executive council. This week he received a very traditional distinction of his own: a knighthood. Yet the organisation he founded, and for which his knighthood is a gong of respect, has probably done more than any single body to upend the traditions of misery and poverty in Bangladesh. Called BRAC, it is by most measures the largest, fastest-growing non-governmental organisation (NGO) in the world—and one of the most businesslike.

Although Mohammed Yunus won the Nobel peace prize in 2006 for helping the poor, his Grameen Bank was neither the first nor the largest microfinance lender in his native Bangladesh; BRAC was. Its microfinance operation disburses about $1 billion a year. But this is only part of what it does: it is also an internet-service provider; it has a university; its primary schools educate 11% of Bangladesh&aposs children. It runs feed mills, chicken farms, tea plantations and packaging factories. BRAC has shown that NGOs do not need to be small and that a little-known institution from a poor country can outgun famous Western charities. In a book on BRAC entitled “Freedom from Want”, Ian Smillie calls it “undoubtedly the largest and most variegated social experiment in the developing world. The spread of its work dwarfs any other private, government or non-profit enterprise in its impact on development.”

None of this seemed likely in 1970, when Sir Fazle turned Shell&aposs offices in Chittagong into a ruge for victims of a deadly cyclone. BRAC—which started as an acronym, Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee, and became a motto, “building resources across communities”—surmounted its early troubles by combining two things that rarely go together: running an NGO as a business and taking seriously the social context of poverty.

BRAC earns from its operations about 80% of the money it disburses to the poor (the remainder is aid, mostly from Western donors). It calls a halt to activities that require endless subsidies. At one point, it even tried financing itself from the tiny savings of the poor (ie, no aid at all), though this drastic form of self-help proved a step too far: hardly any lenders or borrowers put themselves forward. From the start, Sir Fazle insisted on brutal honesty about results. BRAC pays far more attention to research and “continuous learning” than do most NGOs. David Korten, author of “When Corporations Rule the World”, called it “as near to a pure example of a learning organisation as one is likely to find.”

What makes BRAC unique is its combination of business methods with a particular view of poverty. Poverty is often regarded primarily as an economic problem which can be alleviated by sending money. Influenced by three “liberation thinkers” fashionable in the 1960s—Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire and Ivan Illich—Sir Fazle recognised that poverty in Bangladeshi villages is also a result of rigid social stratification. In these circumstances, “community development” will help the rich more than the poor; to change the poverty, you have to change the society.

That view might have pointed Sir Fazle towards lt-wing politics. Instead, the revolutionary impetus was channelled through BRAC into development. Women became the institution&aposs focus because they are bottom of the heap and most in need of help: 70% of the children in BRAC schools are girls. Microfinance encourages the poor to save but, unlike the Grameen Bank, BRAC also lends a lot to small companies. Tiny loans may improve the lot of an individual or family but are usually invested in traditional village enterprises, like owning a cow. Sir Fazle&aposs aim of social change requires not growth (in the sense of more of the same) but development (meaning new and different activities). Only businesses create jobs and new forms of productive enterprise.

After 30 years in Bangladesh, BRAC has more or less perfected its way of doing things and is spreading its wings round the developing world. It is already the biggest NGO in Afghanistan, Tanzania and Uganda, overtaking British charities which have been in the latter countries for decades. Coming from a poor country—and a Muslim one, to boot—means it is less likely to be resented or called condescending. Its costs are lower, too: it does not buy large white SUVs or employ large white men.

Its expansion overseas may, however, present BRAC with a new problem. Robert Kaplan, an American writer, says that NGOs fill the void between thousands of villages and a remote, often broken, government. BRAC does this triumphantly in Bangladesh—but it is a Bangladeshi organisation. Whether it can do the same elsewhere remains to be seen.

上12下

共2页

阅读全文留学咨询

更多出国留学最新动态,敬请关注澳际教育手机端网站,并可拨打咨询热线:400-601-0022

留学热搜

相关推荐

- 专家推荐

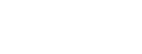

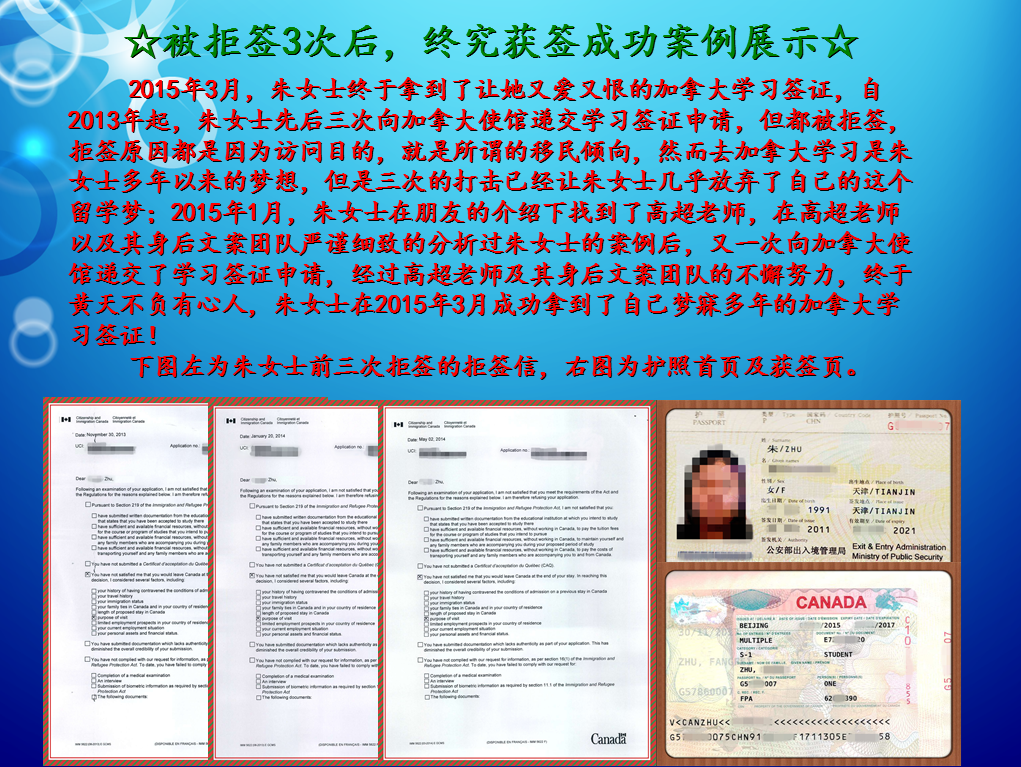

- 成功案例

- 博文推荐

Copyright 2000 - 2020 北京澳际教育咨询有限公司

www.aoji.cn All Rights Reserved | 京ICP证050284号

总部地址:北京市东城区 灯市口大街33号 国中商业大厦2-3层

高国强 向我咨询

行业年龄 13年

成功案例 3471人

留学关乎到一个家庭的期望以及一个学生的未来,作为一名留学规划导师,我一直坚信最基本且最重要的品质是认真负责的态度。基于对学生和家长认真负责的原则,结合丰富的申请经验,更有效地帮助学生清晰未来发展方向,顺利进入理想院校。

Tara 向我咨询

行业年龄 8年

成功案例 2136人

薛占秋 向我咨询

行业年龄 12年

成功案例 1869人

从业3年来成功协助数百同学拿到英、美、加、澳等各国学习签证,递签成功率90%以上,大大超过同业平均水平。

Cindy 向我咨询

行业年龄 20年

成功案例 5340人

精通各类升学,转学,墨尔本的公立私立初高中,小学,高中升大学的申请流程及入学要求。本科升学研究生,转如入其他学校等服务。