2017年12月1日雅思阅读机经.

2017-08-06 371阅读

2012年12月1日的雅思考试过后,澳际小编也在第一时间整理了完整的2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经,在此次的雅思阅读考试的三篇文章中,其中比较典型的几个题型的TRUEFALSENOT GIVEN、Complete table、多选题、Sentence completion的出题比例依旧比较稳定,可以看到判断TRUEFALSENOT GIVEN还是2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经中的重头戏。

| 考试日期: | 2012年12月1日 |

| Reading Passage 1 | |

| Title: | Children Education |

| Question types: | 段落大意 Heading Matching人名理论配对 |

| 文章内容回顾 | 关于儿童教育的(划分了childhood和adulthood, 有了新的政策,很多学者的理论以及发展,幼儿园的发展。从18世纪开始,到19世纪一直到20世纪对children和儿童教育观点的变化,以及为何18世纪一直到1850s家长都不会对自己的孩子倾注太多的感情和澳际(因为儿童死亡率太高);人是可以通过后天教育改变的并不是出身就注定的;20世纪幼儿园的建立和蓬勃发展。旧文V090905的P1 |

| 英文原文阅读 | We examine the prediction of individuals’ educational and occupational success at age 48 from contextual and personal variables assessed during their middle childhood and late adolescence. We focus particularly on the predictive role of the parents’ educational level during middle childhood, controlling for other indices of socioeconomic status and children’s IQ, and the mediating roles of negative family interactions, childhood behavior, and late adolescent aspirations. Data come from the Columbia County Longitudinal Study, which began in 1960 when all 856 third graders in a semi-rural county in New York State were interviewed along with their parents; participants were reinterviewed at ages 19, 30, and 48 (Eron et al, 1971; Huesmann et al., 2002). Parents’ educational level when the child was 8 years old significantly predicted educational and occupational success for the child 40 years later. Structural models showed that parental educational level had no direct fects on child educational level or occupational prestige at age 48 but had significant indirect fects that were independent of the other predictor variables’ fects. These indirect fects were mediated through age 19 educational aspirations and age 19 educational level. These results provide strong support for the unique predictive role of parental education on adult outcomes 40 years later and underscore the developmental importance of mediators of parent education fects such as late adolescent achievement and achievement-related aspirations. Parental educational level is an important predictor of children’s educational and behavioral outcomes (Davis-Kean, 2005; Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2002; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; Haveman & Wolfe, 1995; Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Smith, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1997). The majority of research on the ways in which parental education shapes child outcomes has been conducted through cross-sectional correlational analyses or short-term longitudinal designs in which parents and children are tracked through the child’s adolescent years. Our main goals in the current study were to examine long-term fects on children’s educational and occupational success of their parents’ educational level while controlling for other indices of family socioeconomic status and the children’s own intelligence, and to examine possible mediators of the fects of parents’ education on children’s educational and occupational outcomes. Following theory and research on family process models (e.g., Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1989), we expected that indices of family socioeconomic status, including parent education, would predict the quality of family interactions and child behavior. Next, based on social-cognitive-ecological models (e.g., Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Huesmann, 1998; Huesmann, Eron, & Yarmel, 1987), we expected parental education, the quality of family interactions, and child behavior would shape, by late adolescence, educational achievement and aspirations for future educational and occupational success. Finally, following Eccles’ expectancy-value model (Eccles, 1993; Frome & Eccles, 1998), we predicted that late adolescent aspirations for future success would affect actual educational and occupational success in adulthood. We use data from the Columbia County Longitudinal Study, a 40-year developmental study initiated in 1960 with data collected most recently in 2000 (Eron, Walder, & Lkowitz, 1971; Lkowitz, Eron, Walder, & Huesmann, 1977; Huesmann, Dubow, Eron, Boxer, Slegers, & Miller, 2002; Huesmann, Eron, Lkowitz, & Walder, 1984). Go to: Family Contextual Influences during Middle Childhood In terms of socioeconomic status (SES) factors, the positive link between SES and children’s achievement is well-established (Sirin, 2005; White, 1982). McLoyd’s (1989; 1998) seminal literature reviews also have documented well the relation of poverty and low socioeconomic status to a range of negative child outcomes, including low IQ, educational attainment and achievement, and social-emotional problems. Parental education is an important index of socioeconomic status, and as noted, it predicts children’s educational and behavioral outcomes. However, McLoyd has pointed out the value of distinguishing among various indices of family socioeconomic status, including parental education, persistent versus transitory poverty, income, and parental occupational status, because studies have found that income level and poverty might be stronger predictors of children’s cognitive outcomes compared to other SES indices (e.g., Duncan et al., 1994; Stipek, 1998). Thus, in the present study, we control for other indices of socioeconomic status when considering the fects of parental education. In fact, research suggests that parental education is indeed an important and significant unique predictor of child achievement. For example, in an analysis of data from several large-scale developmental studies, Duncan and Brooks-Gunn (1997) concluded that maternal education was linked significantly to children’s intellectual outcomes even after controlling for a variety of other SES indicators such as household income. Davis-Kean (2005) found direct fects of parental education, but not income, on European American children’s standardized achievement scores; both parental education and income exerted indirect fects on parents’ achievement-fostering behaviors, and subsequently children’s achievement, through their fects on parents’ educational expectations. Thus far, we have focused on the literature on family SES correlates of children’s academic and behavioral adjustment. However, along with those contemporaneous links between SES and children’s outcomes, longitudinal research dating back to groundbreaking status attainment models (e.g, Blau & Duncan, 1967; Duncan, Featherman, & Duncan, 1972) indicates clearly that family of origin SES accounts meaningfully for educational and occupational attainment during late adolescence and into adulthood (e.g., Caspi, Wright, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998; Johnson et al., 1983; Sowski & Amato, 2005; for a review, see Whitson & Keller, 2004). For example, Caspi et al. reported that lower parental occupational status of children ages 3–5 and 7–9 predicted a higher risk of the child having periods of unemployment when making the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Johnson et al. (1983) found that mothers’ and fathers’ educational level and fathers’ occupational status were related positively to their children’s adulthood occupational status. Few studies, however, are prospective in nature spanning such a long period of time (i.e., a 40-year period from childhood to middle adulthood). Also, few studies include a wide range of contextual and personal predictor variables from childhood and potential mediators of the fects of those variables from adolescence. Go to: Potential Mediators of the Effects of Family Contextual Influences during Childhood on Adolescent and Adult Outcomes Family process models (e.g., Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1989; Mistry, Vanderwater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002) have proposed that the fects of socioeconomic stress (e.g., financial strain, unstable employment) on child outcomes are mediated through parenting stress and family interaction patterns (e.g., parental depressed mood; lower levels of warmth, nurturance, and monitoring of children). That is, family structural variables such as parental education and income affect the level of actual interactions within the family, and concomitantly, the child’s behavior. It is well established within broader social learning models (e.g., Huesmann, 1998) that parents exert substantial influence on their children’s behavior. For example, children exposed to more rejecting and aggressive parenting contexts, as well as interparental conflict, display greater aggression (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Eron et al., 1971; Huesmann et al., 1984; Lkowitz et al., 1977) and the fects between negative parenting and child aggression are bi-directional (Patterson, 1982). Presumably, children learn aggressive problem-solving styles as a result of repeated exposure to such models, and in turn parents use more power assertive techniques to manage the child’s behavior. Researchers also have shown that behavioral problems such as early aggression impair children’s academic and intellectual development over time (e.g., Hinshaw, 1992; Huesmann, Eron, & Yarmel, 1987). Stipek (1998) has argued that behavioral problems affect young children’s opportunities to learn because these youth often are punished for their behavior and might develop conflictual relationships with teachers, thus leading to negative attitudes about school and lowered academic success. Thus, it is possible that low socioeconomic status (including low parental educational levels) could affect negative family interaction patterns, which can influence child behavior problems (measured in our study by aggression), and in turn affect lowered academic and achievement-oriented attitudes over time. Parent education and family interaction patterns during childhood also might be linked more directly to the child’s developing academic success and achievement-oriented attitudes. In the general social learning and social-cognitive framework (Bandura, 1986), behavior is shaped in part through observational and direct learning experiences. Those experiences lead to the formation of internalized cognitive scripts, values, and belis that guide and maintain behavior over time (Anderson & Huesmann, 2003; Huesmann, 1998). According to Eccles (e.g., Eccles, 1993; Eccles, Vida, & Barber, 2004; Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiele, 1998), this cognitive process accounts for the emergence and persistence of achievement-related behaviors and ultimately to successful achievement. Eccles’ framework emphasizes in particular the importance of children’s expectations for success, with parents assuming the role of “expectancy socializers” (Frome & Eccles, 1998, p. 437). Thus, for example, a child exposed to parents who model achievement-oriented behavior (e.g., obtaining advanced degrees; reading frequently; encouraging a strong work ethic) and provide achievement-oriented opportunities (e.g., library and museum trips; after-school enrichment programs; educational books and videos) should develop the guiding beli that achievement is to be valued, pursued, and anticipated. This beli should then in turn promote successful outcomes across development, including high school graduation, the pursuit of higher learning, and the acquisition of high-prestige occupations. Not surprisingly, there are positive relations between parents’ levels of education and parents’ expectations for their children’s success (Davis-Kean, 2005), suggesting that more highly educated parents actively encourage their children to develop high expectations of their own. Importantly, on the other hand, McLoyd’s (1989) review found that parents who experience difficult economic times have children who are more pessimistic about their educational and vocational futures. In the current study, we assume a broad social-cognitive-ecological (Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group, 2002; also “developmental-ecological,” Dodge & Pettit, 2003) perspective on behavior development. This view proposes that it is the cumulative influence both of childhood environmental-contextual factors (e.g., parental education, family interactions, school climate, neighborhood ficacy) and individual-personal factors (e.g., IQ and aggression) that shapes enduring cognitive styles (e.g., achievement orientation, hostile worldview) in adolescence. Once formed, those styles allow for the prediction of functioning into adulthood above and beyond the fects of the earlier influences. In this view, then, cognitive factors such as belis and expectations present during adolescence serve as internal links between early contextual and personal factors and later outcomes. |

| 题型难度分析 | 此文不难,是旧文。Heading题考察skim能力,难度不大,但得分率不高。人名理论配对有一定难度。 |

| 题型技巧分析 | 标题配对题(List of headings)是雅思阅读中的一种重要题型,要求给段落找小标题。它一般位于文章之前,由两部分组成:一部分是选项,另一部分是段落编号,要求给各个段落找到与它对应的选项,即表达了该段中心思想的选项,有时还会举一个例子。当然,例子中的选项是不会作为答案的。 解题思路: 1. 将例子所对应的选项及段落标号划去 2. 划出选项中的关键词及概念性名词 3. 浏览文章,抓住各段的主题句和核心词(尤其是反复出现的核心词),重点关注段落首句、第二句与末句 4. 与段落主题句同义或包含段落核心词的选项为正确答案 |

| 剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑5 Early Childhood Education |

| Reading Passage 2 | |

| Title: | Animals’ self-medication |

| Question types: | 判断 细节配对 which paragraph contains the following information |

| 文章内容回顾 | 动物可以通过吃某些植物来缓解病痛,动物用植物和粘土治病,以及对人类研究药物的启发。鹦鹉吃clay, 为了中和它们食物中不好的东西。某日本科学家发现他观察的黑猩猩中有个母的生病了在吃个什么植物然后好了,然后他的向导告诉他那个植物是当地部落人用来驱寄生虫的。科学家继而想到多年前的一个事,好像是猴子把另一种植物卷起来吃。但研究表明那种植物本身并没用药用价值,但把它们刚吃进去的拿来化验发现带有寄生虫,原来是那种植物表面带绒毛还是小刺,可以附着寄生虫,于是把它们gut里的寄生虫都带走了。类似的研究在那期间有不少,但大家都没有互相了解,所以某机构把它们都统一收集起来(有相关题,统一收集起来就是在这一段)。那就出现了新的问题,动物的这种行为究竟是天生的还是模仿的?模仿的例子:小老鼠;天生的例子:鹦鹉吃clay, 即使之前并没有见到clay。旧文V110115的P2 |

| 英文原文阅读 | What do wild animals do when they get sick? Unlike domestic pets, animals in the wild don’t have access to the range of treatments provided by owners or vets. Do wild animals know how to heal themselves? Growing scientific evidence indicates that animals do indeed have knowledge of natural medicines. In fact, they have access to the world&aposs largest pharmacy: nature itself. Zoologists and botanists are only just beginning to understand how wild animals use plant medicines to prevent and cure illness. There’s a name for it The emerging science of Zoopharmacognosy studies how animals use leaves, roots, seeds and minerals to treat a variety of ailments. Indigenous cultures have had knowledge of animal self-medication for centuries; many folk remedies have come from noticing which plants animals eat when they are sick. But it is only in the last 30 years that zoopharmacognosy has been scientifically studied. Biologists witnessing animals eating foods not part of their usual diet, realized the animals were self-medicating with natural remedies. When a pregnant African elephant was observed for over a year, a discovery was made. The elephant kept regular dietary habits throughout her long pregnancy but the routine changed abruptly towards the end of her term. Heavily pregnant, the elephant set off in search of a shrub that grew 17 miles from her usual food source. The elephant chewed and ate the leaves and bark of the bush, then gave birth a few days later. The elephant, it seemed, had sought out this plant specifically to induce her labor. The same plant (a member of the borage family) also happens to be brewed by Kenyan women to make a labor-inducing tea. Chimps take their medicine Not only do many animals know which plant they require, they also know exactly which part of the plant they should use, and how they should ingest it. Chimpanzees in Tanzania have been observed using plants in different ways. The Aspilia shrub produces bristly leaves, which the chimps carully fold up then roll around their mouths bore swallowing whole. The prickly leaves &aposscour&apos parasitical worms from the chimps intestinal lining. The same chimps also peel the stems and eat the pith of the Vernonia plant (also known as Bitter leaf). In bio-chemical research, Vernonia was found to have anti-parasitic and anti-microbial properties. Both Vernonia and Aspilia have long been used in Tanzanian folk medicine for stomach upsets and fevers. It is only the sick chimpanzees that eat the plants. The chimps often grimace as they chew the Vernonia pith, indicating that they are not doing this for fun; healthy animals would find the bitter taste unpalatable. Nature’s pharmacy for all Wild animals won’t seek out a remedy unless they need it. Scientists studying baboons at the Awash Falls in Ethiopia noted that although the tree Balanites aegyptiaca (Desert date) grew all around the falls, only the baboons living below the falls ate the tree’s fruit. These baboons were exposed to a parasitic worm found in water-snails. Balanites fruit is known to repel the snails. Baboons living above the falls were not in contact with the water-snails and therore had no need of the medicinal fruit. Many animals eat minerals like clay or charcoal for their curative properties. Colobus monkeys on the island of Zanzibar have been observed stealing and eating charcoal from human bonfires. The charcoal counteracts toxic phenols produced by the mango and almond leaves which make up their diet. Some species of South American parrot and macaw are known to eat soil with a high kaolin content. The parrots’ diet contains toxins because of the fruit seeds they eat. (Even the humble apple seed contains cyanide.) The kaolin clay absorbs the toxins and carries them out of the birds&apos digestive systems, leaving the parrots unharmed by the poisons. Kaolin has been used for centuries in many cultures as a remedy for human gastrointestinal upset. Survival of the medicated So, how do animals know how to heal themselves? Some scientists believe that evolution has given animals the innate ability to choose the correct herbal medicines. In terms of natural selection, animals who could find medicinal substances in the wild were more likely to survive. Other observations have shown that, particularly among primates, medicinal skills appear to be taught and learned. Adult females are often seen batting their infant&aposs hand from a particular leaf or stem as if to say “No, not that one.” Wild animals don’t rely on industrially produced synthetic drugs to cure their illnesses; the medicines they require are available in their natural environment. While animals in the wild instinctively know how to heal themselves, humans have all but forgotten this knowledge because of our lost connection with nature. Since wild animals have begun to be observed actively taking care of their own wellbeing, it raises questions of how we approach healthcare with natural remedies, not just for ourselves but for our companion and farm animals too. |

| 题型难度分析 | 判断题难度不大,难点在于细节配对,建议细节配对放在最后做。 |

| 题型技巧分析 | 是非无判断题是上半年度的重点题型,有顺序原则。 注意看清是TRUE还是YES, 本篇是TRUE/ FALSE/ NOT GIVEN 解题步骤: 1. 速读句子,找出考点词(容易有问题的部分)。考点词:比较级,最高级,数据(时间),程度副词,特殊形容词,绝对化的词(only,most,each,any,every,the same as等) 2. 排除考点词,在余下的词中找定位词,去原文定位。 3. 重点考察考点词是否有提及,是否正确。 TRUE的原则是同义替换,至少有一组近义词。 FALSE是题目和原文截然相反,不可共存,通常有至少一组反义词。 NOT GIVEN原文未提及,不做任何推断,尤其多考察题目的主语等名词在原文是否有提及。 4. 通读所有段落,依次寻找答案 因为每段都会有答案,因此现在所需要做的事情就是到每段去找答案。要注意在选出信息后,要在选出的段落上做上记号,以免浪费时间。 段落细节信息配对题 1. 无序 2. 注意有可能出现NB 3. 注意大量题目和原文的近义替换 |

| 剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑7 test1 passage 1 Let’s go bats |

| Reading Passage 3 | |

| Title: | Art |

| Question types: | 判断 配对 |

| 文章内容回顾 | 关于托尔斯泰的艺术观,即关于艺术的本质问题。讲他对艺术是什么观点。他最大的贡献不在于给出了艺术的定义,而是在于提出了一系列问题如何去判断一个作品是否属于art。他认为艺术家应该是业余的,不应该是职业化的,还批判了传统的主流观点关于构成艺术作品的要素,例如beauty, entertainment什么的;然后继续批判很多传统的艺术品都是counterfeit的,这些作品都有“imitation", "striking"等特点。 |

| 英文原文阅读 | According to Tolstoy, art must create a specific emotional link between artist and audience, one that "affects" the viewer. Thus, real art requires the capacity to unite people via communication (clearness and genuineness are therore crucial values). This aesthetic conception led Tolstoy to widen the criteria of what exactly a work of art is. He believed that the concept of art embraces any human activity in which one emitter, by means of external signs, transmits previously experienced feelings. Tolstoy offers an example of this: a boy that has experienced fear after an encounter with a wolf later relates that experience, infecting the hearers and compelling them to feel the same fear that he had experienced—that is a perfect example of a work of art. As communication, this is good art, because it is clear, it is sincere, and it is singular (focused on one emotion). However, genuine "infection" is not the only criterion for good art. The good art vs. bad art issue unfolds into two directions. One is the conception that the stronger the infection, the better is the art. The other concerns the subject matter that accompanies this infection, which leads Tolstoy to examine whether the emotional link is a feeling that is worth creating. Good art, he claims, fosters feelings of universal brotherhood. Bad art inhibits such feelings. All good art has a Christian message, because only Christianity teaches an absolute brotherhood of all men. However, this is "Christian" only in a limited meaning of the word. Art produced by artistic elites is almost never good, because the upper class has entirely lost the true core of Christianity. Furthermore, Tolstoy also believed that art that appeals to the upper class will feature emotions that are peculiar to the concerns of that class. Another problem with a great deal of art is that it reproduces past models, and so it is not properly rooted in a contemporary and sincere expression of the most enlightened cultural ideals of the artist&aposs time and place. To cite one example, ancient Greek art extolled virtues of strength, masculinity, and heroism according to the values derived from its mythology. However, since Christianity does not embrace these values (and in some sense values the opposite, the meek and humble), Tolstoy believes that it is unfitting for people in his society to continue to embrace the Greek tradition of art. Among other artists, he specifically condemns Wagner and Beethoven as examples of overly cerebral artists, who lack real emotion. Furthermore, Beethoven&aposs Symphony No. 9 cannot claim to be able to "infect" its audience, as it pretends at the feeling of unity and therore cannot be considered good art. |

| 题型难度分析 | 判断和配对题是经典的搭配,前者相比之下,稍微容易,是应该把握分数之处。 |

| 题型技巧分析 | 段落细节配对难度较大,建议考生放在本篇文章所有题型的最后去做。做时注意切不可逐题去原文整篇文章搜寻答案,这样会导致文章来来回回看很多遍,耗时太长。 1. 划出所有题目的keywords, 同时考虑到有可能出现近义替换的词,有针对性的去原文寻找答案。比如:看到be conscious of立刻想到雅思高频近义替换是be aware of…, 看到reproduce想到copy。 2. 某些题目可以对题目进行细致的分析。平时通过精读多多熟悉文章结构安排,了解行文模式。 3. 做题时以文章为基准,每看一段,浏览题目中的keywords是否与其相关。 |

| 剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑4 The Aim and Nature of Archaeology |

|

考试趋势分析和备考指导:

1. heading题卷土重来,预测继11月份后,依然是12月考试的主题。 2. 配对继续延续本年度最热题型,尤其是细节配对,是考生们复习的重点也是难点。 3. 判断题的题量持续稳定,三篇中有两篇都有,所以考生们应在判断题中多拿分数。 4. 文章话题中,讲述某门专业的(如此次的art)向来有一定难度,学会把握文章结构和背景知识很重要。 5. 有旧话题和文章的出现,考生应多关注机经和剑桥系列真题文章。 |

|

以上就是澳际小编整理的2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经全部内容,可以看出此次的雅思阅读机经中题型的分布还是比较典型,很有代表性的,希望同学们在通过雅思阅读机经备考的过程中,要注意各类题型的解题方法以及出现频率。

2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经2012年12月1日的雅思考试过后,澳际小编也在第一时间整理了完整的2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经,在此次的雅思阅读考试的三篇文章中,其中比较典型的几个题型的TRUEFALSENOT GIVEN、Complete table、多选题、Sentence completion的出题比例依旧比较稳定,可以看到判断TRUEFALSENOT GIVEN还是2012年12月1日雅思阅读机经中的重头戏。

| 考试日期: | 2012年12月1日 |

| Reading Passage 1 | |

| Title: | Children Education |

| Question types: | 段落大意 Heading Matching人名理论配对 |

| 文章内容回顾 | 关于儿童教育的(划分了childhood和adulthood, 有了新的政策,很多学者的理论以及发展,幼儿园的发展。从18世纪开始,到19世纪一直到20世纪对children和儿童教育观点的变化,以及为何18世纪一直到1850s家长都不会对自己的孩子倾注太多的感情和澳际(因为儿童死亡率太高);人是可以通过后天教育改变的并不是出身就注定的;20世纪幼儿园的建立和蓬勃发展。旧文V090905的P1 |

| 英文原文阅读 | We examine the prediction of individuals’ educational and occupational success at age 48 from contextual and personal variables assessed during their middle childhood and late adolescence. We focus particularly on the predictive role of the parents’ educational level during middle childhood, controlling for other indices of socioeconomic status and children’s IQ, and the mediating roles of negative family interactions, childhood behavior, and late adolescent aspirations. Data come from the Columbia County Longitudinal Study, which began in 1960 when all 856 third graders in a semi-rural county in New York State were interviewed along with their parents; participants were reinterviewed at ages 19, 30, and 48 (Eron et al, 1971; Huesmann et al., 2002). Parents’ educational level when the child was 8 years old significantly predicted educational and occupational success for the child 40 years later. Structural models showed that parental educational level had no direct fects on child educational level or occupational prestige at age 48 but had significant indirect fects that were independent of the other predictor variables’ fects. These indirect fects were mediated through age 19 educational aspirations and age 19 educational level. These results provide strong support for the unique predictive role of parental education on adult outcomes 40 years later and underscore the developmental importance of mediators of parent education fects such as late adolescent achievement and achievement-related aspirations. Parental educational level is an important predictor of children’s educational and behavioral outcomes (Davis-Kean, 2005; Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2002; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; Haveman & Wolfe, 1995; Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Smith, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1997). The majority of research on the ways in which parental education shapes child outcomes has been conducted through cross-sectional correlational analyses or short-term longitudinal designs in which parents and children are tracked through the child’s adolescent years. Our main goals in the current study were to examine long-term fects on children’s educational and occupational success of their parents’ educational level while controlling for other indices of family socioeconomic status and the children’s own intelligence, and to examine possible mediators of the fects of parents’ education on children’s educational and occupational outcomes. Following theory and research on family process models (e.g., Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1989), we expected that indices of family socioeconomic status, including parent education, would predict the quality of family interactions and child behavior. Next, based on social-cognitive-ecological models (e.g., Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Huesmann, 1998; Huesmann, Eron, & Yarmel, 1987), we expected parental education, the quality of family interactions, and child behavior would shape, by late adolescence, educational achievement and aspirations for future educational and occupational success. Finally, following Eccles’ expectancy-value model (Eccles, 1993; Frome & Eccles, 1998), we predicted that late adolescent aspirations for future success would affect actual educational and occupational success in adulthood. We use data from the Columbia County Longitudinal Study, a 40-year developmental study initiated in 1960 with data collected most recently in 2000 (Eron, Walder, & Lkowitz, 1971; Lkowitz, Eron, Walder, & Huesmann, 1977; Huesmann, Dubow, Eron, Boxer, Slegers, & Miller, 2002; Huesmann, Eron, Lkowitz, & Walder, 1984). Go to: Family Contextual Influences during Middle Childhood In terms of socioeconomic status (SES) factors, the positive link between SES and children’s achievement is well-established (Sirin, 2005; White, 1982). McLoyd’s (1989; 1998) seminal literature reviews also have documented well the relation of poverty and low socioeconomic status to a range of negative child outcomes, including low IQ, educational attainment and achievement, and social-emotional problems. Parental education is an important index of socioeconomic status, and as noted, it predicts children’s educational and behavioral outcomes. However, McLoyd has pointed out the value of distinguishing among various indices of family socioeconomic status, including parental education, persistent versus transitory poverty, income, and parental occupational status, because studies have found that income level and poverty might be stronger predictors of children’s cognitive outcomes compared to other SES indices (e.g., Duncan et al., 1994; Stipek, 1998). Thus, in the present study, we control for other indices of socioeconomic status when considering the fects of parental education. In fact, research suggests that parental education is indeed an important and significant unique predictor of child achievement. For example, in an analysis of data from several large-scale developmental studies, Duncan and Brooks-Gunn (1997) concluded that maternal education was linked significantly to children’s intellectual outcomes even after controlling for a variety of other SES indicators such as household income. Davis-Kean (2005) found direct fects of parental education, but not income, on European American children’s standardized achievement scores; both parental education and income exerted indirect fects on parents’ achievement-fostering behaviors, and subsequently children’s achievement, through their fects on parents’ educational expectations. Thus far, we have focused on the literature on family SES correlates of children’s academic and behavioral adjustment. However, along with those contemporaneous links between SES and children’s outcomes, longitudinal research dating back to groundbreaking status attainment models (e.g, Blau & Duncan, 1967; Duncan, Featherman, & Duncan, 1972) indicates clearly that family of origin SES accounts meaningfully for educational and occupational attainment during late adolescence and into adulthood (e.g., Caspi, Wright, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998; Johnson et al., 1983; Sowski & Amato, 2005; for a review, see Whitson & Keller, 2004). For example, Caspi et al. reported that lower parental occupational status of children ages 3–5 and 7–9 predicted a higher risk of the child having periods of unemployment when making the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Johnson et al. (1983) found that mothers’ and fathers’ educational level and fathers’ occupational status were related positively to their children’s adulthood occupational status. Few studies, however, are prospective in nature spanning such a long period of time (i.e., a 40-year period from childhood to middle adulthood). Also, few studies include a wide range of contextual and personal predictor variables from childhood and potential mediators of the fects of those variables from adolescence. Go to: Potential Mediators of the Effects of Family Contextual Influences during Childhood on Adolescent and Adult Outcomes Family process models (e.g., Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1989; Mistry, Vanderwater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002) have proposed that the fects of socioeconomic stress (e.g., financial strain, unstable employment) on child outcomes are mediated through parenting stress and family interaction patterns (e.g., parental depressed mood; lower levels of warmth, nurturance, and monitoring of children). That is, family structural variables such as parental education and income affect the level of actual interactions within the family, and concomitantly, the child’s behavior. It is well established within broader social learning models (e.g., Huesmann, 1998) that parents exert substantial influence on their children’s behavior. For example, children exposed to more rejecting and aggressive parenting contexts, as well as interparental conflict, display greater aggression (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Eron et al., 1971; Huesmann et al., 1984; Lkowitz et al., 1977) and the fects between negative parenting and child aggression are bi-directional (Patterson, 1982). Presumably, children learn aggressive problem-solving styles as a result of repeated exposure to such models, and in turn parents use more power assertive techniques to manage the child’s behavior. Researchers also have shown that behavioral problems such as early aggression impair children’s academic and intellectual development over time (e.g., Hinshaw, 1992; Huesmann, Eron, & Yarmel, 1987). Stipek (1998) has argued that behavioral problems affect young children’s opportunities to learn because these youth often are punished for their behavior and might develop conflictual relationships with teachers, thus leading to negative attitudes about school and lowered academic success. Thus, it is possible that low socioeconomic status (including low parental educational levels) could affect negative family interaction patterns, which can influence child behavior problems (measured in our study by aggression), and in turn affect lowered academic and achievement-oriented attitudes over time. Parent education and family interaction patterns during childhood also might be linked more directly to the child’s developing academic success and achievement-oriented attitudes. In the general social learning and social-cognitive framework (Bandura, 1986), behavior is shaped in part through observational and direct learning experiences. Those experiences lead to the formation of internalized cognitive scripts, values, and belis that guide and maintain behavior over time (Anderson & Huesmann, 2003; Huesmann, 1998). According to Eccles (e.g., Eccles, 1993; Eccles, Vida, & Barber, 2004; Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiele, 1998), this cognitive process accounts for the emergence and persistence of achievement-related behaviors and ultimately to successful achievement. Eccles’ framework emphasizes in particular the importance of children’s expectations for success, with parents assuming the role of “expectancy socializers” (Frome & Eccles, 1998, p. 437). Thus, for example, a child exposed to parents who model achievement-oriented behavior (e.g., obtaining advanced degrees; reading frequently; encouraging a strong work ethic) and provide achievement-oriented opportunities (e.g., library and museum trips; after-school enrichment programs; educational books and videos) should develop the guiding beli that achievement is to be valued, pursued, and anticipated. This beli should then in turn promote successful outcomes across development, including high school graduation, the pursuit of higher learning, and the acquisition of high-prestige occupations. Not surprisingly, there are positive relations between parents’ levels of education and parents’ expectations for their children’s success (Davis-Kean, 2005), suggesting that more highly educated parents actively encourage their children to develop high expectations of their own. Importantly, on the other hand, McLoyd’s (1989) review found that parents who experience difficult economic times have children who are more pessimistic about their educational and vocational futures. In the current study, we assume a broad social-cognitive-ecological (Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group, 2002; also “developmental-ecological,” Dodge & Pettit, 2003) perspective on behavior development. This view proposes that it is the cumulative influence both of childhood environmental-contextual factors (e.g., parental education, family interactions, school climate, neighborhood ficacy) and individual-personal factors (e.g., IQ and aggression) that shapes enduring cognitive styles (e.g., achievement orientation, hostile worldview) in adolescence. Once formed, those styles allow for the prediction of functioning into adulthood above and beyond the fects of the earlier influences. In this view, then, cognitive factors such as belis and expectations present during adolescence serve as internal links between early contextual and personal factors and later outcomes. |

| 题型难度分析 | 此文不难,是旧文。Heading题考察skim能力,难度不大,但得分率不高。人名理论配对有一定难度。 |

| 题型技巧分析 | 标题配对题(List of headings)是雅思阅读中的一种重要题型,要求给段落找小标题。它一般位于文章之前,由两部分组成:一部分是选项,另一部分是段落编号,要求给各个段落找到与它对应的选项,即表达了该段中心思想的选项,有时还会举一个例子。当然,例子中的选项是不会作为答案的。 解题思路: 1. 将例子所对应的选项及段落标号划去 2. 划出选项中的关键词及概念性名词 3. 浏览文章,抓住各段的主题句和核心词(尤其是反复出现的核心词),重点关注段落首句、第二句与末句 4. 与段落主题句同义或包含段落核心词的选项为正确答案 |

| 剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑5 Early Childhood Education |

上123下

共3页

阅读全文留学咨询

更多出国留学最新动态,敬请关注澳际教育手机端网站,并可拨打咨询热线:400-601-0022

留学热搜

相关推荐

- 专家推荐

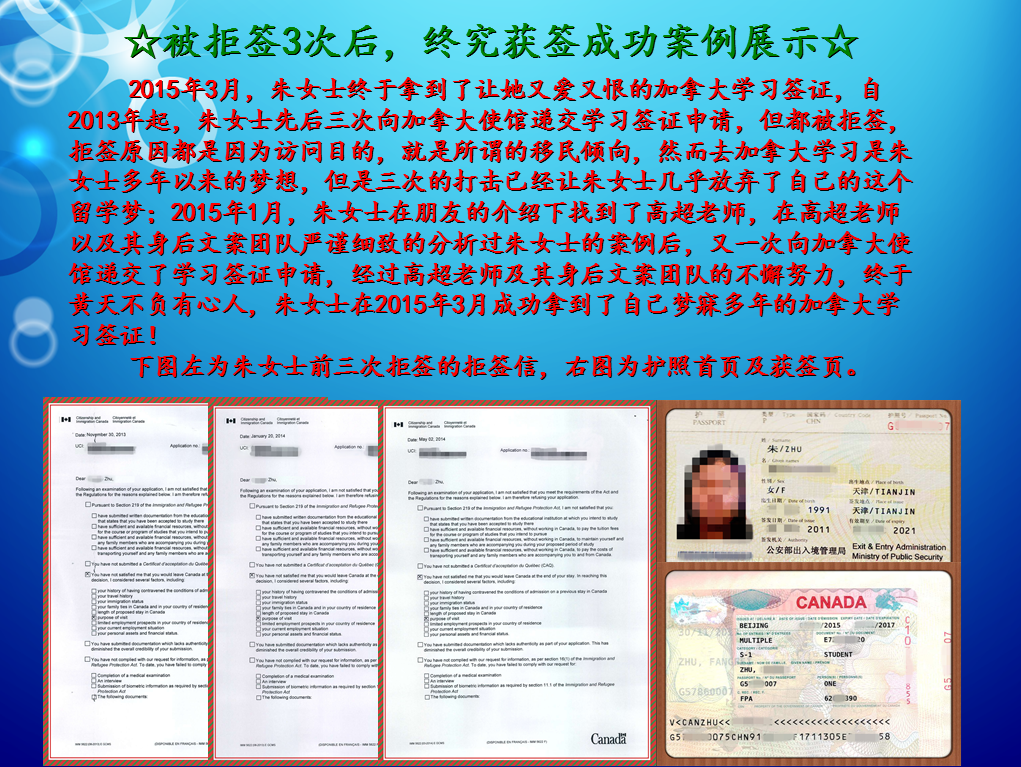

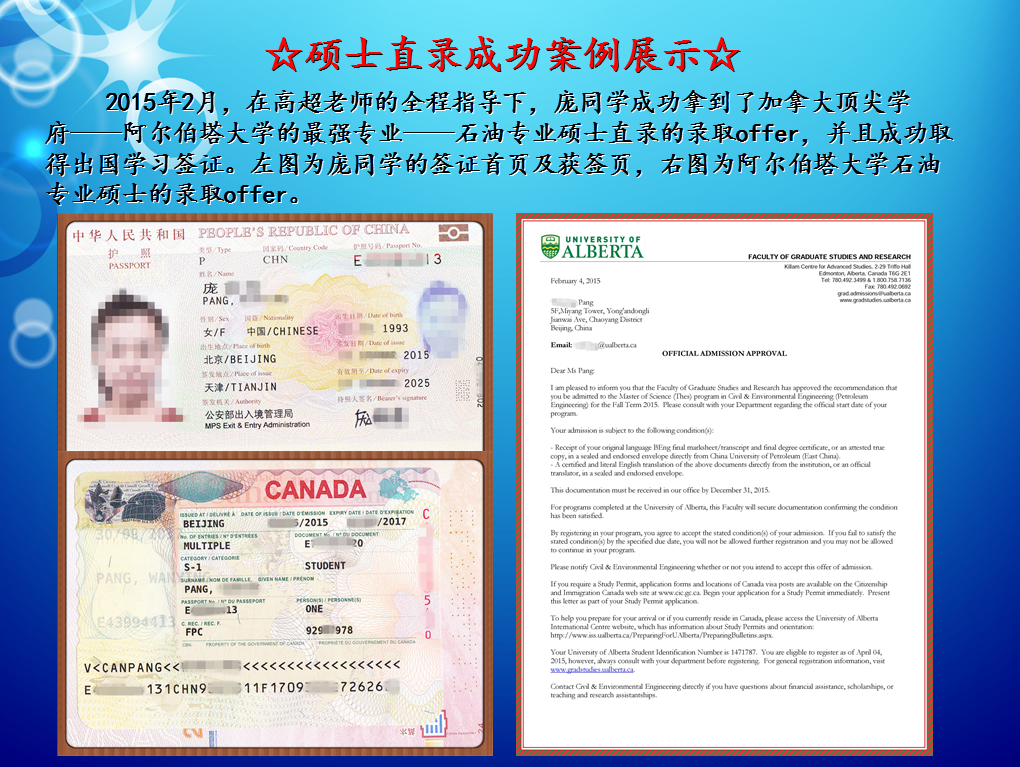

- 成功案例

- 博文推荐

Copyright 2000 - 2020 北京澳际教育咨询有限公司

www.aoji.cn All Rights Reserved | 京ICP证050284号

总部地址:北京市东城区 灯市口大街33号 国中商业大厦2-3层

高国强 向我咨询

行业年龄 11年

成功案例 2937人

留学关乎到一个家庭的期望以及一个学生的未来,作为一名留学规划导师,我一直坚信最基本且最重要的品质是认真负责的态度。基于对学生和家长认真负责的原则,结合丰富的申请经验,更有效地帮助学生清晰未来发展方向,顺利进入理想院校。

Tara 向我咨询

行业年龄 6年

成功案例 1602人

薛占秋 向我咨询

行业年龄 10年

成功案例 1869人

从业3年来成功协助数百同学拿到英、美、加、澳等各国学习签证,递签成功率90%以上,大大超过同业平均水平。

Cindy 向我咨询

行业年龄 18年

成功案例 4806人

精通各类升学,转学,墨尔本的公立私立初高中,小学,高中升大学的申请流程及入学要求。本科升学研究生,转如入其他学校等服务。