2017年9月7日雅思阅读机经整理.

2017-08-06 240阅读

下面是2013年9月7日雅思阅读机经的内容。包括Listening To The Ocean,Children's Comprehension of Advertisement,Remember This这三个部分。下面我们就一起来看看这次考试的雅思阅读考题会给大家带来哪些启发和借鉴呢?

考试日期: | 2013年9月7日 |

Reading Passage 1 | |

Title: | Listening To The Ocean |

Question �types: | 4道段落信息配对;4道是非无判断;5道选择题(4选1); |

文章内容回顾 | 文章主要讲通过声音测海洋深度,制造了一个仪器可以听鲸鱼的动静,可以观察海水温度变化,测定海洋的深度和气候,以及预测“雨的类型”。人们对月亮的观察远远早于对海洋的监测,因为很早的时候就能通过肉眼观测月亮,后来是通过望远镜来观测月亮,但是光线却难以穿透海水,使得人们对海洋的了解十分有限,后来xx开始用声音来探测海洋,并介绍了声音和光在物理性质上的相似性。海洋的温度、盐度等都会影响声音在海洋中的传播速度。长声波在海洋中可以传播得更远;xx组织发明了声纳用于探测海洋,这个声纳从船上发出和接收声波,科学家们在不同位置接收声波来探测海洋的各方面指数,可以用来追踪鲸鱼,而且可以同时追踪多个,Fine whale在不同季节会发出不同calls, 海洋可以影响气候,比如El �Nino. |

题型难度分析 | 第一篇的题型包括4道段落信息配对,4道TRUE/FALSE/NOT GIVEN和5道4选1的选择题,从难度上来讲,有一定难度,因为段落信息配对题的题目顺序与文章顺序不一致,需要对全文通读,后面两题的难度一般。 |

题型技巧分析 | 对于词汇量大和阅读理解速度较快的同学,建议先做第一题,然后再做后面两道题,这样做的目的是:做完第一题可以对整篇文章有一个较清晰的认识,再做后面两道题时会比较轻松。 对于词汇量不大、阅读理解速度较慢的同学,建议先做后面两道题,不要在第一道题目上花费太多时间,这样会得不偿失,花了大量的时间却得不到好的结果。 |

剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑桥真题7 Test 2 |

Reading Passage 2 | |

Title: | Children's Comprehension of Advertisement |

Question �types: | List Of Heading; TRUE / FALSE / NOT GIVEN; Summary填空题; |

文章内容回顾 | 文章介绍了电视广告对于儿童的各种影响和各种不同的商业广告是如何通过各种方法来实现推销产品的目的的。文中两次提到了Macdonald's的广告,还提到了其他的广告;其次文章引用了多位学者对于电视广告的不同理论观点,用科学方法表明4-5岁以下的儿童,对广告只是停留在欣赏其中的画面的层面,他们是无法区分广告和电视节目的区别的,所以成年人最好能告诉孩子关于广告的事实真相。Summary题目主要集中在文章后半部分,其中最后一个空格有些跨度,但答案可以显然推出是shorter。 |

题型难度分析 | 中等难度 |

题型技巧分析 | 标题配对题(List of headings)是雅思阅读中的一种重要题型,要求给段落找小标题。它一般位于文章之前,由两部分组成:一部分是选项,另一部分是段落编号,要求给各个段落找到与它对应的选项,即表达了该段中心思想的选项,有时还会举一个例子。当然,例子中的选项是不会作为答案的。 解题思路: 1. 将例子所对应的选项及段落标号划去 2. 划出选项中的关键词及概念性名词 3. 浏览文章,抓住各段的主题句和核心词(尤其是反复出现的核心词),重点关注段落首句、第二句与末句 4. 与段落主题句同义或包含段落核心词的选项为正确答案 Summary填空题有几个特别重要的技巧: 做题之前先判断所填词的词性,如果空格前面出现了“the, a, an”, 那么文章中需要填的词前面一般也会出现这三个冠词。 如果题目所在句子里出现了“逻辑关系”,那么文章中相对应的句子里也会出现同样的“逻辑关系”。 |

剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑桥真题8 Test 2 |

Reading Passage 3 | |

Title: | Remember This |

Question �types: | Summary选词填空题;人名+理论配对题;选择题; |

文章内容回顾 | 文章中给出的研究,是基于AJ, �EP两位患者有关记忆的两个极端案例:一个人的记忆力好到超乎想象,他几乎可以记得生命中发生的每一件事;而另外一个人的记忆力非常差,差到甚至连刚刚发生的事情都记不起来。介绍了一位神经外科医生相关的research, 还有现代医药在人类记忆领域方面所作出的研究和努力。三大题型中,summary多集中在文章前几段落;选择题从文章第八段开始,遵循每段一题的原则,定位明确,语言简单,答案显见。 |

相关英文原文阅读 | There is a �41-year-old woman, an administrative assistant from California known in the medical �literature only as "AJ," who remembers almost every day of her life �since age 11. There is an 85-year-ol man, a retired lab technician called "EP," �who remembers only his most recent thought. She might have the best memory in �the world. He could very well have the worst. AJ and EP are �extremes on the spectrum of human memory. And their cases say more than any brain �scan about the extent to which our memories make us who we are. Though the rest �of us are somewhere between those two poles of remembering everything and nothing, �we've all experienced some small taste of the promise of AJ and dreaded the fate �of EP. Those three pounds or so of wrinkled flesh balanced atop our spines can �retain the most trivial details about childhood experiences for a lifetime but �often can't hold on to even the most important telephone number for just two minutes. �Memory is strange like that. What is a memory? �The best that neuroscientists can do for the moment is this: A memory is a stored �pattern of connections between neurons in the brain. There are about a hundred �billion of those neurons, each of which can make perhaps 5,000 to 10,000 synaptic �connections with other neurons, which makes a total of about five hundred trillion �to a thousand trillion synapses in the average adult brain. By comparison there �are only about 32 trillion bytes of information in the entire Library of Congress's �print collection. Every sensation we remember, every thought we think, alters �the connections within that vast network. Synapses are strengthened or weakened �or formed anew. Our physical substance changes. Indeed, it is always changing, �every moment, even as we sleep. A Canadian �neurosurgeon named Wilder Penfield thought he'd proved that theory by the 1940s �after using electrical probes to stimulate the brains of epileptic patients while �they were lying conscious on the operating table. He was trying to pinpoint the �source of their epilepsy, but he found that when his probe touched certain parts �of the temporal lobe, the patients started describing vivid experiences. When �he touched the same spot again, he often elicited the same descriptions. Penfield �came to believe that the brain records everything to which it pays any degree �of conscious attention, and that this recording is permanent. Most scientists �now agree that the strange recollections triggered by Penfield were closer to �fantasies or hallucinations than to memories, but the sudden reappearance of long-lost �episodes from one's past is an experience surely familiar to everyone. Still, �as a recorder, the brain does a notoriously wretched job. Tragedies and humiliations �seem to be etched most sharply, often with the most unbearable exactitude, while �those memories we think we really need—the name of the acquaintance, the time �of the appointment, the location of the car keys—have a habit of evaporating. Michael Anderson, �a memory researcher at the University of Oregon in Eugene, has tried to estimate �the cost of all that evaporation. According to a decade's worth of "forgetting �diaries" kept by his undergraduate students (the amount of time it takes �to find the car keys, for example), Anderson calculates that people squander more �than a month of every year just compensating for things they've forgotten. It would seem �as though having a memory like AJ's would make life qualitatively different—and �better. Our culture inundates us with new information, yet so little of it is �captured and cataloged in a way that it can be retrieved later. What would it �mean to have all that otherwise lost knowledge at our fingertips? Would it make �us more persuasive, more confident? Would it make us, in some fundamental sense, �smarter? To the extent that experience is the sum of our memories and wisdom the �sum of experience, having a better memory would mean knowing not only more about �the world, but also more about oneself. How many worthwhile ideas have gone unthought �and connections unmade because of our memory's shortcomings? After Simonides' �discovery, the art of memory was codified with an extensive set of rules and instructions �by the likes of Cicero and Quintilian and in countless medieval memory treatises. �Students were taught not only what to remember but also techniques for how to �remember it. In fact, there are long traditions of memory training in many cultures. �The Jewish Talmud, embedded with mnemonics—techniques for preserving memories—was �passed down orally for centuries. Koranic memorization is still considered a supreme �achievement among devout Muslims. Traditional West African griots and South Slavic �bards recount colossal epics entirely from memory. K. Anders Ericsson, �a professor of psychology at Florida State University, believes that at bottom, �AJ might not be all that different from the rest of us. After the initial announcement �of AJ's condition in the journal Neurocase, Ericsson suggested that what needs �to be explained about AJ is not some extraordinary, unprecedented innate memory �but rather her extraordinary obsession with her past. People always remember things �that are important to them. Baseball fanatics often have an encyclopedic knowledge �for statistics, chess masters often remember tricky gambits that took place years �ago, actors often remember scripts long after performing them. Everyone has got �a memory for something. Ericsson believes that if anyone cared about holding on �to the past as much as AJ does, the feat of memorizing one's life would be well �within reach. Harvard psychologist �Daniel Schacter has developed a taxonomy of forgetting to catalog what he calls �the seven sins of memory. The sin of absentmindedness: Yo-Yo Ma forgetting his �2.5-million-dollar cello in the back of a taxi. The Vietnam War veteran still �haunted by the battlield suffers from the sin of persistence. The politician �who loses a word on the tip of his tongue during a stump speech is experiencing �the sin of blocking. Though we curse these failures of memory on an almost daily �basis, Schacter says, that's only because we don't see their benits. Each sin �is really the flip side of a virtue, "a price we pay for processes and functions �that serve us well in many respects." There are good evolutionary reasons �why our memories fail us in the specific ways they do. If everything we looked �at, smelled, heard, or thought about was immediately filed away in the enormous �database that is our long-term memory, we'd be drowning in irrelevant information. Within the �past decades, drug companies have elevated the search to brave new heights. Armed �with a sophisticated understanding of memory's molecular underpinnings, they've �sought to create new drugs that amplify the brain's natural capacity to remember. �In recent years, at least three companies have been formed with the express purpose �of developing memory drugs. One of those companies, Cortex Pharmaceuticals, is �attempting to develop a class of molecules known as ampakines, which facilitate �the transmission of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Glutamate is one of the primary �excitatory chemicals passed across the synapses between neurons. By amplifying �its fects, Cortex hopes to improve the brain's underlying ability to form and �retrieve memories. When administered to middle-age rats, one ampakine was able �to fully reverse their age-related decline in the cellular mechanism of memory. All of this �raises some troubling ethical questions. Would we choose to live in a society �where people have vastly better memories? In fact, what would it even mean to �have a better memory? Would it mean remembering things only exactly as they happened, �free from the revisions and exaggerations that our mind naturally creates? Would �it mean having a memory that forgets traumas? Would it mean having a memory that �remembers only those things we want it to remember? Would it mean becoming AJ? |

题型难度分析 | 本篇文章中出现了Summary选词填空题和“人名+理论配对题”,总体难度相对而言中等。 |

题型技巧分析 | 在做雅思人名观点配对题时不需要看完全篇再去做题,而是可以采用定位法去解决,这样既快捷高效地完成了阅读任务,也不会再对阅读中的搭配题感到棘手和害怕。 一、考题要点 A. 人名观点配对一般考察的是某个人的言论(statement)、观点(opinion)、评论(comment)、发现(findings �or discoveries)。这样,一般这个题的答案在文中就只有两个答案区: 1. 人名边上的引号里面的内容; 2. 人名+ �think /say /claim /argue /believe /report /find /discover /insist /admit /report... �+ that从句。 B. 人名在文中一般以以下方式出现: 1. 全称(full �name), 如:Brian Waldron 2. 名(first �name), 不常见 3. 姓(surname), 如:Professor �Smith 4. He/she(在同一段话中,该人再次出现时,用指示代词替代) 因此,建议考生去文中找人名时,应该将上述四种情况均考虑进去。再者,应该谨记在心的是:如果一个人名在一段话中出现N次,也只能算一次。如果一个人名在N段话中出现,就算N次。 C. 该题的答案遍布于全文。因此应该从文章的开头往后依次寻找人名。 D. 该题貌似是对全篇文章的考察,其实考察的就是这些人所说的几句话。故应先从文中找人名,再去找答案。 |

剑桥雅思推荐原文练习 | 剑桥真题5 Test 4 |

考试趋势分析和备考指导: 1. 9月份首场考试,并没有出现传说中的变题,考生普遍反映本次阅读比课堂练习的官方真题难度偏小。所以考生尽量还是紧跟专业老师的指导意见,以主流题型为主。 2. 配对题型,尤其是段落信息配对、人名+理论配对,仍旧是接下来考试的重点题型;接下来的考生应该重点复习LOH, 未完成句配对。 3. 此外,9月份后面的考试,考生要重点复习填空类型的题目,如:完成句子填空、简答题、图表填空等。 4. 本次考试,在文章题材上属于科学类、人类发展类、社会儿童类。在后面的考试中可以着重复习工农业类型话题,如C7T1P2; 自然科学类话题,如C7T3P1, C8T4P3; 语言文化类话题,如C4T2P1, C5T2P3; 传记类和发明类文章,如C5T1P1, C5T2P1, C8。 | |

以上就是雅思阅读机经的相关介绍,分享给大家,希望对大家有所帮助,最后祝大家都能考出好成绩。

留学咨询

更多出国留学最新动态,敬请关注澳际教育手机端网站,并可拨打咨询热线:400-601-0022

留学热搜

相关推荐

- 专家推荐

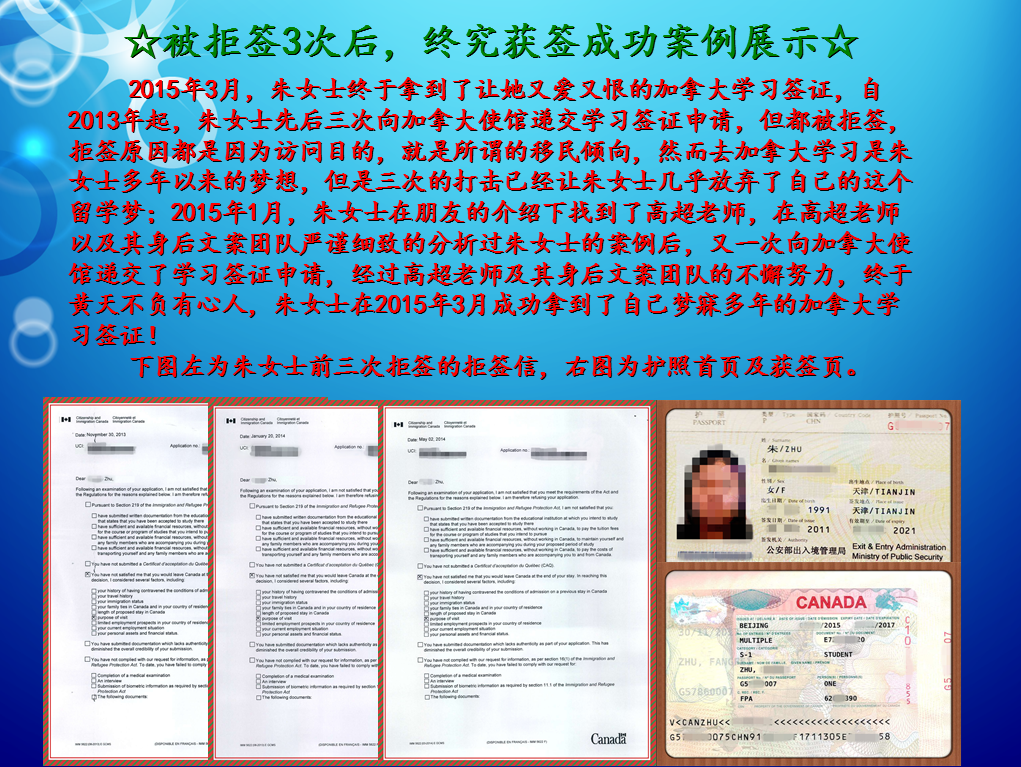

- 成功案例

- 博文推荐

Copyright 2000 - 2020 北京澳际教育咨询有限公司

www.aoji.cn All Rights Reserved | 京ICP证050284号

总部地址:北京市东城区 灯市口大街33号 国中商业大厦2-3层

Tara 向我咨询

行业年龄 8年

成功案例 2136人

Cindy 向我咨询

行业年龄 20年

成功案例 5340人

精通各类升学,转学,墨尔本的公立私立初高中,小学,高中升大学的申请流程及入学要求。本科升学研究生,转如入其他学校等服务。

薛占秋 向我咨询

行业年龄 12年

成功案例 1869人

从业3年来成功协助数百同学拿到英、美、加、澳等各国学习签证,递签成功率90%以上,大大超过同业平均水平。

Amy GUO 向我咨询

行业年龄 18年

成功案例 4806人

熟悉澳洲教育体系,精通各类学校申请程序和移民局条例,擅长低龄中学公立私立学校,预科,本科,研究生申请